UNDERSTANDING THE TECHNOLOGY OF THE DARAKI-CHATTAN CUPULES: THE CUPULE REPLICATION PROJECT

Giriraj Kumar and Ram Krishna

Abstract. The Lower Palaeolithic cupules in the small cave of Daraki-Chattan are of different shapes and sizes. How they were made is the subject of this investigation. The hardness of the quartzite rock of the cave adds to the complexities in understanding the production process.

The study of the more than 500 cupules on the vertical walls of the cave is a joint venture of Indian and Australian scientists, the EIP Project. The senior author commenced a program of replicating the cupules, in an effort to understand the circumstances of their creation, on an experimental rock panel close to Daraki-Chattan in 2002. The project of replicating different kinds of cupules encountered in Daraki-Chattan has been continued since then and was joined by the second author in 2004. This paper presents the gist of the replication project from 2002

to 2012.

Introduction

Daraki-Chattan is a small, narrow and deep cave in quartzite buttresses of Indragarh Hill near Bhanpura, district Mandsaur in Madhya Pradesh, India (Fig. 1). It was discovered by our friend Ramesh Kumar Pancholi in 1993 (Pancholi 1994). The cave is slightly more than 4.0 m wide at the dripline, and 1.4 m at its mouth. From here it continuously narrows down in width, to 34 cm at a depth of 7.4 m, it then becomes slightly wider, up to 40 cm, finally closing at the depth of 8.4 m from its mouth. The cave is maximal 7.4 m in height. It bears more than five hundred cupules on both of its vertical walls. A cupule is a petroglyph of hemispherical shape or its variation, created by percussion technique on a horizontal, inclined or vertical rock surface. The cave overlooks the valley of the river Rewa which opens in front of it into nearly 3-km-wide

agricultural fields. The area was a dense forest with rich fauna including tigers even just 50 years back, in the 1960s. The hills and their foothills on both sides of the river were also a rich source of quartzite for manufacturing of stone artefacts by hominins in the Lower Palaeolithic, as indicated by extensive surface occurrences of artefact scatters as well as in stratified exposures. We discovered early Acheulian factory sites with finished artefacts, big flakes and cores from nearby, especially from the foothill on the opposite hill on the right bank of the river and on the Chanchalamata Hill near Daraki-Chattan. We also discovered Acheulian artefacts on the plateau of Indragarh Hill above the cave, as well as artefacts representing the transitional phase from Lower to Middle Palaeolithic industries from inside the cave. No other artefacts of later cultural phases were found in Daraki-Chattan in 1994–95, hence one of us postulated that the cupules inside the cave may belong to the Acheulian or the following transitional phase (Kumar 1995, 1996).

Figure 1. Daraki-Chattan Cave in the quartzite buttresses

of Indragarh Hill in Chambal basin, central India.

Most of the first half portion of the southern wall is devoid of cupules on its surface (Fig. 2). It must have been exfoliated and fallen below and become stratified. This meant that the sloping sediments in front of the cave should contain pieces of cupule-bearing slabs and also some of the hammerstones used for their production. Both were indeed amply found during excavations (Kumar et al. 2005; Bednarik et al. 2005).

Figure 2. Part of southern wall of Daraki-Chattan near entrance,

bearing hundreds of cupules.

The EIP Project

In order to study the early cupules in India and establishing their antiquity the EIP Project was established during the Third AURA Congress at Alice Springs in 2000. Its name is an acronym of Early Indian Petroglyphs: Scientific Investigation and Dating by International Commission. It is a joint venture by Indian and Australian scientists conducted in collaboration of RASI and AURA under the aegis of IFRAO, with Giriraj Kumar and Robert G. Bednarik as its Indian and Australian directors. It has been supported and supervised by the Archaeological Survey of India. Support was also given by the Indian Council of Historical Research and the Australia-India Council, Canberra.

Under the EIP Project excavations were carried out at Daraki-Chattan for five seasons from 2002 to 2006, under the supervision of the first author (Kumar et al. 2005; Kumar 2006), and 325-cm-thick sediments were excavated. The preliminary results of the EIP Project have been published in India, Australia and other countries from time to time (Kumar et al. 2002, 2005, 2012; Kumar 2008, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Bednarik et al. 2005; Bednarik 2009a, 2012; Bednarik and Kumar 2012; Krishna and Kumar 2012a, 2012b, 2012c). However, a summary of the excavations is provided here to define the typological-cultural development of lithics and correlation of the exfoliated cupules and hammerstones found in different layers with them.

Summary of the excavations

The Lower Palaeolithic stone tool sequence in the Daraki-Chattan sediments commences from the uppermost levels of the floor deposit, which comprises only a very thin layer of more recent strata. In places an industry intermediate to Middle and Lower Palaeolithic (MP and LP) typology was visible at the surface before excavation commenced. These intermediate tool types are underlain by a substantial deposit defined as Acheulian, but poor in typical handaxes and cleavers. Six vague and fairly arbitrary layers were distinguished in the sediment, becoming progressively more reddish in layer 5 (Bednarik et al. 2005: Fig. 26). The lowest sediment deposit is characterised by its red colour, the upper part of which contains severely weathered Mode 1 cobble tools as well as hammerstones of the type used to produce the cupules (Figs 3–5, 8a).

Arbitrary sediment layers 3 and 4 contain LP flake artefacts, some made from river cobbles, but most made of the local purplish quartzite. A few artefacts consist of deeply patinated cherts. Layer 5 contains still much the same industry, but increasing iron content has effected a more reddish colour. Both stone tools and clasts show increasing effects of weathering and iron induration with greater depth, which on large clasts may take the form of thick mineral crusts of primarily ferromanganese composition.

The basal sediment layer features only very weathered stone tools and clasts. Tool types from the lower sediments include cobble tools, discoids, core choppers, flake scrapers and polyhedrons similar to the so-called Durkadian (for references for the following summary see Bednarik 2009b; Bednarik and Kumar 2012). A few specimens resemble what have been called corescrapers at Mahadeo-Piparia, another central Indian site, whose repertoire has been called the Mahadevian. These characteristic pieces are large blocks with a zigzagging edge produced by chunky flakes having been removed alternatively from each side.

Although LP and MP stone-tool traditions are widespread in India, represented in massive quantities and typologically accounted for, their absolute chronology has remained largely unresolved so far. This is due both to a paucity of excavated sites (most known sites are surface scatters) and a pronounced lack of well-dated sites. The cobble or chopping tools preceding the bifaces of the Indian Acheulian have attracted comparatively little attention.

While the Lower Acheulian remains largely un-dated, preliminary indications suggest a late Middle Pleistocene antiquity for the Final

Acheulian. Thorium-uranium dates from three calcareous conglomerates containing Acheulian artefacts (Nevasa, Yedurwadi, Bori) suggest ages in the order of 200 ka. The most recent date for an Indian Acheulian deposit is currently the uranium-series result of about 150 ka from a conglomerate travertine at Kaldevanahalli. There remains wide disagreement about the antiquity of the Early Acheulian and the Mode 1 industries. Some favour a date of 1.4 million years (Ma) from Kukdi valley for the earliest phase of the Acheulian; others reject it. The earliest phase of human presence in India, of Mode 1 assemblages, remains largely undated, but at Pabbi Hills, dates ranging from 2.2 to 1.2 Ma have been acquired by palaeomagnetism. The few flaked quartzite cobbles from Riwat (Pakistan) appear to be in the order of 2.5 Ma old, rather than 1.9 Ma as previously proposed. The claims from Labli Uttarani, ranging from 1.6 to 2.8 Ma, are viewed sceptically. However, the earliest data from China imply an occupation by hominins prior to 2 Ma, which presumes human presence in India by that time. Reliably identified Mode 1 industries have been excavated from secure stratigraphies in very few cases, and they were found below Mode 2 (Acheulian) strata at the two early cupule sites, Auditorium Cave at Bhimbetka and Daraki-Chattan. These quartzite tools are partially decomposed at both sites and they were found in both cases below pisoliths and heavy ferromanganese mineral accretions indicating a significant climatic incursion. Details of the typological context of the excavated tools from Daraki-Chattan have been published by Bednarik and Kumar (2012: 154–55, in CD pp. 895–906).

The excavations at Daraki-Chattan have established that the cave was a Lower Palaeolithic occupation site (Figs 3 and 4). During the excavations exfoliated cupules and hammerstones used for the creation of cupules (Fig. 5) were obtained from arbitrary layer 3 down to arbitrary layer 4, 5 and from the interface of 6/5 (Bednarik et al. 2005: Fig. 26). It means the cupules on the excavated slabs must have been much older than their stratigraphical antiquity, and this applies also to the cupules on the cave walls. Thus, the EIP Project has confirmed the evidence of Lower Palaeolithic cupules for the first time in the world.

It also established that with more than five hundred cupules on both vertical walls, Daraki-Chattan is the richest known early Palaeolithic cupule site in the world (Fig. 2) (Kumar 1995, 1996, 2006; Kumar et al. 2005; Bednarik et al. 2005).

Figure 3. Excavations at Daraki-Chattan: section facing south.

Figure 4. Daraki-Chattan: Oldowan type chopper on quartzite from

the lower-most level of pseudo-layer 5.

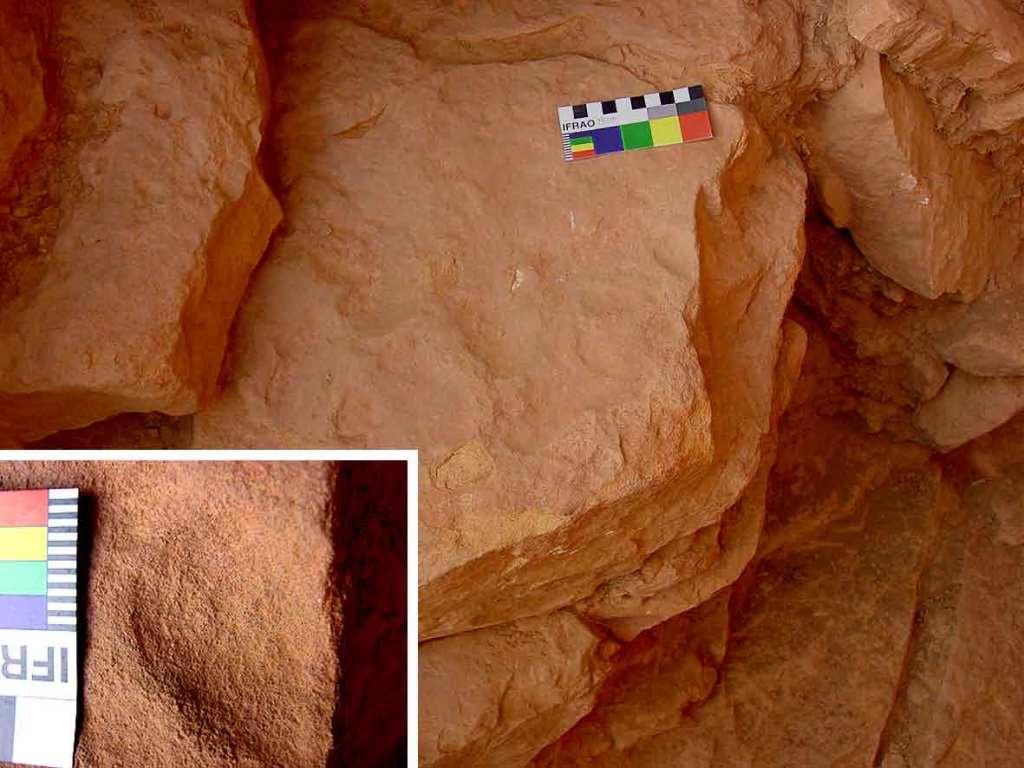

Figure 5. A slab lying close to bedrock in pseudo-layer 5/6 bearing an

oval/elliptical cupule (broken); inset close-up of the same.

Figure 6. Big circular cupules on northern wall.

In addition to housing some of the oldest known rock art, Daraki-Chattan is also an important Palaeolithic site because it is one of the very few Indian locations where Mode 1 (pre-Acheulian) occupation evidence has been excavated in a stratified context. Overlain by a typical Acheulian with handaxes, this deposit has yielded very simple, Oldowan-like stone artefacts made mostly of the local quartzite. This very early cupule site is therefore of particular importance to exploring the LP industries of southern Asia (Bednarik and Kumar 2012: 154–155, in CD pp. 895–906).

Questions raised by Daraki-Chattan

The high concentration of cupules in a small cave such as Daraki-Chattan requires an explanation. The hardness of the quartzite rock of the cave adds more complexities to its understanding. Common questions being raised in reference to this site are:

1. How were these cupules made on such a hard quartzite rock?

2. Were these cupules the creation of a single period or were they made in different periods, and when were they made?

3. Do the cupules in Daraki-Chattan show a diachronic development?

4. What was the purpose of creating such a large number of cupules on such a small and narrow cave?

5. What is the significance of the study of these cupules?

Until c. 2001 it was impossible to answer such questions scientifically. The study of the early petroglyphs through the EIP Project has focused on being able to answer some of these questions.

Study of the cupules

We made a preliminary study of the cupules in Daraki-Chattan Cave while documenting them in 1994–95 (see Kumar 1996: Figs 5, 6). However, for understanding the creation of cupules in Daraki-Chattan through replication it was necessary to understand the cupule forms more closely.

Categories of cupule forms in Daraki-Chattan

We studied and documented 496 cupules on both walls of Daraki-Chattan Cave in 1995. Out of these, 402 cupules are circular or almost circular, 85 are elongated (oval) and 9 are more angular in shape. Of the circular cupules we distinguished two categories in 1995: (1) saucer-shaped big circular cupules, and (2) bowl-shaped big circular cupules (Kumar 1995). However, later on we observed that circular cupules have one more category: circular cupules with conical section (Kumar and Prajapati 2010; Krishna and Kumar

2012a).

Almost all the cupules and the bedrock around them bear light-brown patina. Most of them also bear mineral encrustation and also show different stages of weathering. Later on a few more cupules have been observed near the roof of the cave on the southern wall, and two on the bedrock of the cave floor. Besides, slabs bearing 28 cupules were excavated during 2002–2006, out of which two cupules were in situ (Kumar et al. 2012).

The archaic cupules in Daraki-Chattan Cave have now been classified broadly into four categories with their sub-categories as follows (Kumar and Prajapati 2010; Krishna and Kumar 2012a):

1. Big circular cupules with saucer-shaped floor or deeply rounded floor (Fig. 6):

1a. Big circular cupules of more than 50 mm diameter and smooth saucer-shaped floor, of more than 5 mm depth.

1b. Big and deep cupules of about 30 to 50 mm diameter and 7 to 12 mm depth, smooth and rounded floor; sometimes the depth is more than 12 mm.

2. Cupules with conical section:

2a. Circular cupules of about 30 to 40 mm diameter and conical section of more than 5 mm depth (Fig. 7).

2b. Oval or elongate cupules with oblique and conical section, deepest point is always below the cupule’s centre (Fig. 8).

3. Small cupules:

3a. Small circular and shallow cupules which appear to be unfinished.

3b. Small circular cupules with deep smooth floor. Figure 6. Big circular cupules on northern wall.

Examples on the northern wall (NR): NR 144; 24.65 × 27.0 × 11; 35 mm, deep conical cupule. NR 162. 24.5 × 23. 8 × 8. 83 mm. On southern wall: SR 195b. 32.3 × 24.6 × 8.4 mm.

4. Small cupules with angular periphery and deep angular section. They are rare:

(1) Northern wall, on the lower side before Group 1a: 18.3 × 17.6 × 5.7 mm, with roughly triangular periphery and angular section (it is a new cupule observed on northern wall of the cave on 27 December 2008, hence has no number).

(2) SR 23 (Fig. 9); 27.3 ×24.6 × 8.4 mm, with roughly triangular periphery and roughly triangular section. It is the only case of its kind and is exceptionally difficult to produce.

(3) However, in the study of the cupules in DC in January 2012 we observed a few more specimens with angular periphery. Near the distal end of the southern wall, cupule SR 174 is deep and with roughly square periphery (Fig. 10). It could be identified on close observation. Close to and slightly below it, cupule SR 200 is roughly triangular in shape with weathered base facing upwards and rounded upper half. Cupule SR 193 is located slightly above, and close to it on its left side is a big version of cupule SR 200 (Krishna and Kumar 2012b).

Categories 1 and 2 form the major bulk of the cupules in Daraki-Chattan Cave. Category 3 forms only a small part, while cupules of category 4 are rare. Cupules of category 2 have been found from the excavations at Daraki-Chattan.

Replication of cupules

In the global literature (Bednarik 1998: 23–35) on rock art we do not have any reference for replication work that could have helped us in understanding the techniques used, cognition and skill required and complexities involved in producing the cupules on hard quartzite rock. Hence, in order to understand the creation of cupules and their significance in Daraki-Chattan we have been experimenting with the replication of cupules on a selected vertical wall in a rockshelter closely associated with and located by the right side (south) of Daraki-Chattan (Fig. 11). It is a continuation of the same quartzite bedrock forming Daraki-Chattan.

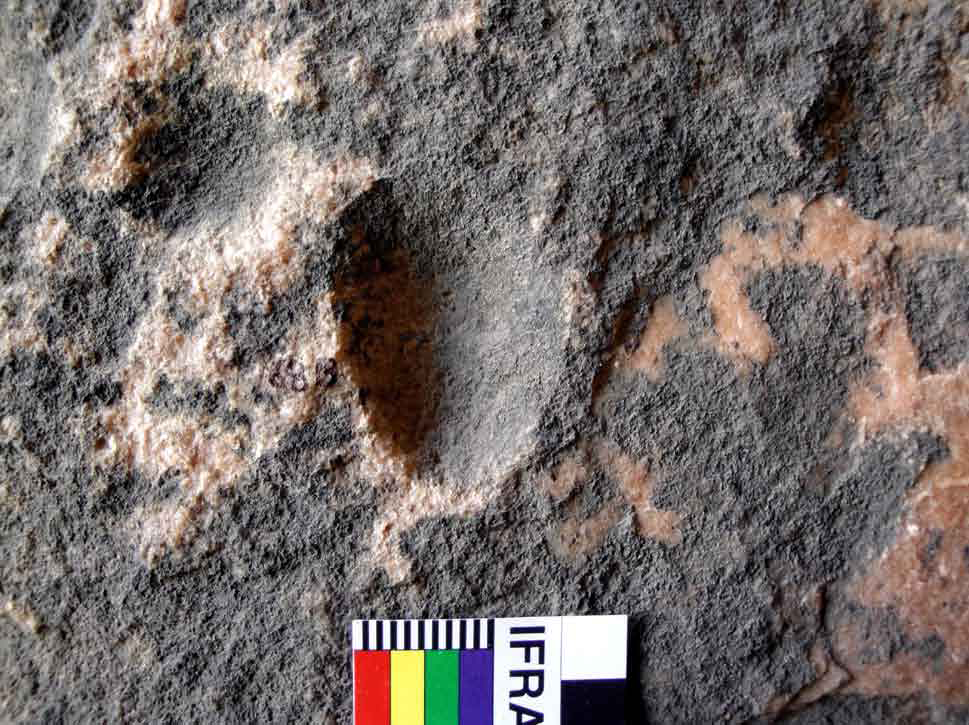

Figure 9. Roughly triangular cupule No. 23 southern

wall.

Figure 10. Roughly square shape cupule with angular

depth, No. 174 on southern wall.

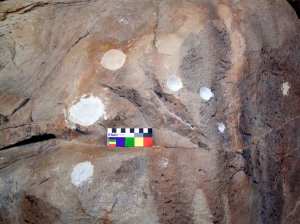

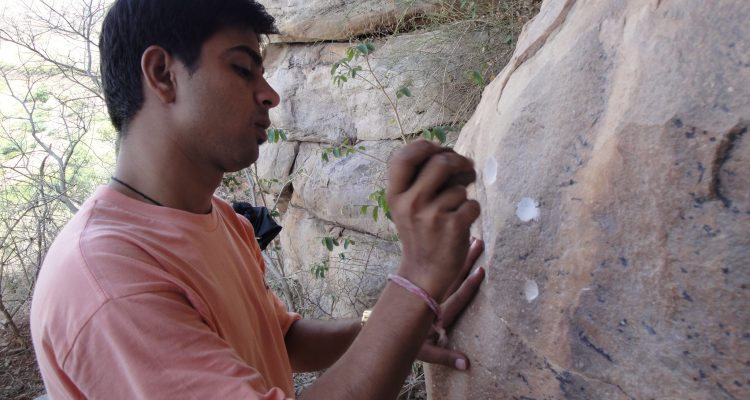

Figure 11. Experimental rock in a rockshelter by the southern side of Daraki-Chattan (left), and some of the replica cupules on it (right).

The rockshelter, 660 cm in breadth at the dripline, 175 cm deep and 275 cm in height at present, faces west. The vertical wall of the shelter runs 210 cm from north to south, than turns to southeast for an additional distance of 140 cm. It is 200 cm in height from the present floor surface.

We really need to show how hard it is to make the described different types of cupules and how much deliberate effort is required in their production. Secondly, we also need to understand and justify the nature and types of hammerstones discovered in the excavations at Daraki-Chattan and correlate them with the cupules in the cave (Fig. 12). Experiment with replication of cupules was commenced by GK in 2002, the year of beginning the excavation at Daraki-Chattan. Ram Krishna (Prajapati) joined the replication project in 2004. It is still continuing (Kumar and Prajapati 2010; Krishna and Kumar 2012a, 2012b, 2012c). So far we have replicated ten cupules.

Hammerstones used for practical work

Pebbles and cobbles from a nearby site, Patasighati, with purple-red coloured core, are very hard and are most suitable for use as hammerstones

for cupule production and also to make artefacts from. They are of greater density than the bedrock of Daraki-Chattan. They were similarly used at this place by hominins in the Lower Palaeolithic. We also experimented with hammerstones on chert, chalcedony, and basalt and other igneous rocks, but they were not found suitable because of their fragile nature. Patasighati is located in between Indragarh Hill and Chanchalamata Hill. It contains highly cemented thick boulder conglomerate of river deposit in a palaeochannel. So far we could not find any stone artefact or fossil remains from this palaeochannel deposit. It must have been formed by a very powerful stream of very high kinetic intensity, as the boulders up to 50 cm diameter have become almost round, some are flat and round, hence the local name Patasighati (valley of boulders, cobbles and pebbles like sugar cakes).

Technique used

From the study and observation of the hardness of the bedrock and smoothness of the archaic cupules in Daraki-Chattan, GK believed intuitively from the very beginning that these could have been produced by direct percussion technique; hence he used the same technique for cupule replication unless mentioned otherwise.

Summary of the replication project, study and observations to date

The details of our replication project on different shapes and size of cupules (Figs 13–17) and the shape of different hammerstones after their use (Fig. 18–21) have been reported from time to time (Kumar 2010c; Kumar and Prajapati 2010; Krishna and Kumar 2012a, 2012b, 2012c). Hence, instead of giving these details we are presenting here a summary and a comparative study of the replication process in Table 1. It is followed by our understanding of the creation of different cupule forms and overall observation on the skill, efficiency and cognitive state of their authors.

Table 1: Comparative study of the production process and observations on the replicated cupules, and comments on them. Read More

Comments:

Our replication experiments on hard quartzite rock by the side of DC from 2002 to 2012 have revealed some facts about the creation of different forms of cupules in Daraki-Chattan Cave which are as follows:

1. It is incredibly hard to replicate cupules on hard quartzite rock. Besides, it requires immense skill and precision.

2. Big circular cupules. In Daraki-Chattan, cupules of category 1a, i.e. big circular cupules of more than 50 mm diameter, more than 5 mm deep and saucer shaped, appear to be the work more of strength and commitment and less of skill. They were produced by using a very simple technology of direct percussion. They appear to represent the earliest stage of cupule production. Our cupule replication experiment indicates that to produce cupules of category 1a needs two to six hammerstones on cobbles to produce such cupules, depending on the quality of the stone used and the strength of the person at work. It is a tough and tedious task to produce a cupule on hard quartzite rock, requiring motivation, commitment, strength, endurance and patience for its production.

3. Small circular cupules with conical section. We successfully replicated such cupules in December 2008 and June 2009. They appear to be the work of modified technology of direct percussion with small hammerstones of specific shape and size. It requires proper planning, immense skill and great precision and patience to produce such cupules. The person at work on cupule production cannot afford a wrong stroke, even in a thousand, as it increases the diameter of the cupule. Thus, these cupules are a work of modified technology and advanced skill and precision and great concentration and patience. Their creation needs comparatively light strokes and use of multiple hammerstones. It also reflects a tradition of long experience.

4. Elongated cupules are the result of further experiments with small circular cupules with conical section.

5. Roughly triangular cupules. A small cupule with conical section produced by direct percussion forms the base to produce a roughly triangular form of cupule. If the centre of the depth is shifted, the cupule form will change to a roughly triangular form. It is the main finding of our study of the cupules in Daraki-Chattan, their close observation and discussion followed by replication work during January 2012. Further, it needs individual innovation and reflects on the advanced stage of the cognitive development of its author. Its production requires light strokes applied over longer time, compared to small circular cupules with conical section.

6. Study and understanding of the creation of roughly angular form of cupules may help to understand the invention and development of geometrical forms, especially the triangular and square forms in terms of antiquity in the Stone Age. It will also help in understanding the antiquity of the cognitive and cultural development of their authors.

7. Cupule creation is definitely not a leisure work or ludic. It is a very tough job and appears to be closely associated with something special and deeply significant.

8. Cupule replication is found to be an important method for understanding the process and technique of cupule creation, in the present case on hard quartzite rock. It renders hypotheses testable; hence it is an important scientific exercise.

Conclusions

1. In addition to housing some of the oldest known rock art in the world, Daraki-Chattan is also an important Palaeolithic occupation site because it is one of the very few Indian locations where Mode 1 (pre-Acheulian) occupation evidence has been excavated in a stratified context. Overlain by a typical Acheulian with handaxes, this deposit has yielded very simple, Oldowan-like stone artefacts made mostly of the local quartzite. This very early cupule site is therefore of particular importance to exploring the Lower Palaeolithic industries of southern Asia (Bednarik and Kumar 2012).

Small elongated hammerstone Hs-2, used in stage 2 of the

production of RC-10.

2. It is incredibly hard to replicate cupules on hard quartzite rock. Besides, it requires immense skill and precision.

3. The replication of cupules helped us in understanding that their creation on hard quartzite rock is a very long, hard and labour-consuming task, involving literally tens of thousands of strokes with hammerstones. The struck rock being very hard, the hammerstone rebounds with equal force with each stroke, and gives a powerful jerk in the shoulder of the worker, especially in case of cupule replication of categories 1a and 2a. Hence, the person working on replication of cupule creation must have sufficient physical strength, commitment, stamina and patience.

4. Big circular cupules, small circular cupules with conical depth and roughly triangular cupules created by direct percussion method may reflect a steady advancement in technology, skill, precision, intelligence and cognitive development in early human history of the Pleistocene. It appears phenomenon more of the social and cultural environment and also that of opportunities and encouragement provided by the social groups rather than evolution of skill in different species of the Homo. The same is the case even at present when we observe the development of juveniles in rural and urban environment in different parts of the world. We can also recall the Industrial Revolution and development of bicycles, motor bikes, cars, aeroplanes etc., from their modest forms in the beginning to the modern advanced forms of the present. The underlying nature of the culture of our ancestors was not significantly different in a qualitative sense from our own. Of course in the Stone Age the development was a slow process. Different technologies, designs, devices and equipment were developed according to the need of the time to make the tasks comparatively easy and life more comfortable. Thus, cupule creation of different forms by early humans appears to be related to cultural evolution deeply embedded in the cognitive development in hominins.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely extend our heartfelt thanks to the four scholars for reviewing the paper as RAR referees and for their constructive suggestions, most of which have been taken careof in the final version of this paper.

Professor Giriraj Kumar

Faculty of Arts Dayalbagh Educational Institute, Dayalbagh, Agra 282 005

India

girirajrasi.india@gmail.com

Ram Krishna

Ramkrishna.gem@gmail.com

Final MS received 12 November 2013.

References

Bednarik, R. G. 1998. The technology of petroglyphs. Rock Art Research 15: 23–35.

Bednarik, R. G. 2009a. Lower and Middle Palaeolithic palaeoart of the world. Paper presented in Symposium

4: recent trends in word rock art research, in the IFRAO Congress ‘Global Rock Art’ held at Capivara, Saõ Raimundo Noñato, Piauí, Brazil, from 29 June to 3 July 2009.

Bednarik, R. G. 2009b. The global context of Lower Palaeolithic Indian palaeoart. Man and Environment 34(2): 1–16.

Bednarik, R. G. 2012. Dating and taphonomy of Pleistocene rock art. In J. Clottes (ed.), L’art pléistocène dans de monde, Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarascon-sur-Ariège, septembre 2010, Special issue, Préhistoire, Art et Sociétés, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées LXV–LXVI: 188–189 (1059–1060 on CD).

Bednarik, R. G. 2012. Indian Pleistocene rock art in the global context. In J. Clottes (ed.), L’art pléistocène dans de monde, Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarascon-sur-Ariège, septembre 2010, Special issue, Préhistoire, Art et Sociétés, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées LXV–LXVI: 150–151 (869–878 on CD).

Bednarik, R. G. and G. Kumar 2012. Typological context of the Lower Palaeolithic lithics from Daraki-Chattan Cave, India. In J. Clottes (ed.), L’art pléistocène dans de monde, Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarascon-sur-Ariège, septembre 2010, Special issue, Préhistoire, Art et Sociétés, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées LXV–LXVI: 154-155 (895–906 on CD).

Bednarik, R. G., G. Kumar, A. Watchman and R. G. Roberts 2005. Preliminary results of the EIP Project. Rock Art Research 22: 147–197.

Krishna, R. and G. Kumar 2012a. Understanding the creation of small conical cupules in Daraki-Chattan. In J. Clottes (ed), L’art pléistocène dans de monde, Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarascon-sur-Ariège, septembre 2010, Special issue, Préhistoire, Art et Sociétés, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées LXV–LXVI: pp. 216–217 (1229–1256 on CD).

Krishna, R. and G. Kumar 2012b. Replication of early angular cupules on hard quartzite rock at Daraki-Chattan by direct percussion method. Purakala 22: 17–28.

Krishna, R. and G. Kumar 2012c. Physico-psychological approach for understanding the significance of Lower Palaeolithic cupules. In J. Clottes (ed.), L’art pléistocène dans de monde, Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarascon-sur-Ariège, septembre 2010, Special issue, Préhistoire, Art et Sociétés, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées LXV–LXVI: 156–157 (907–918 on CD).

Kumar, G. 1995. Daraki-Chattan: a Palaeolithic cupule site in India. Purakala 6: 17–28.

Kumar, G. 1996. Daraki-Chattan: a Palaeolithic cupule site in India. Rock Art Research 13: 38–46.

Kumar, G. 2006. A preliminary report of excavations at Daraki-Chattan- 2006. Purakala 16: 51–55.

Kumar, G. 2008. Lower Palaeolithic petroglyphs from excavations at Daraki-Chattan in India. In R. G. Bednarik and D. Hodgson (eds), Pleistocene palaeoart of the world, pp. 63–75. BAR International Series 1804, Archaeopress, Oxford.

Kumar. G. 2010a. Recent developments in rock art research in India with special reference to the EIP Project. In L. M. Olivieri, L. Bruneau and M. Ferrandi (eds), Pictures in transformation: rock art research between central Asia and the subcontinent, pp. 1–12. BAR International Series 2167, Archaeopress, Oxford.

Kumar, G. 2010b. Cognitive and creative abilities of Lower Palaeolithic hominins in India. FUMDHAM Mentos 9: 187–195. Fundaçào Museu do Homen Americano, São Raimundo Noñato, Brazil.

Kumar, G. 2010c. Understanding the creation of early cupules by replication with special reference to Daraki-Chattan in India. In R. Querejazu Lewis and R. G. Bednarik (eds), Mysterious cup marks: proceedings of the First International Cupule Conference, pp. 59–66. BAR International Series 2073, Archaeopress, Oxford.

Kumar, G., R. G. Bednarik, A. Watchman and C. Patterson 2002. 2002- EIP Project report-II: sample collection for analytical study and scientific dating of the early Indian petroglyphs and rock paintings by the international commission. Purakala 13(1–2): 21–28.

Kumar, G., R. G. Bednarik, A. Watchman and R. G. Roberts 2005. The EIP Project in 2005: a progress report. Purakala 14–15: 13–68.

Kumar, G. and R. K. Prajapati 2010. Understanding the creation of cupules in Daraki-Chattan, India. FUMDHAM Mentos 9: 167–186. Fundaçào Museu do Homen Americano, São Raimundo Noñato, Brazil.

Kumar, G., N. Vyas, R. G. Bednarik and A. Pradhan 2012. Lower Palaeolithic petroglyphs and hammerstones obtained from the excavations at Daraki-Chattan Cave in India. In J. Clottes (ed.), L’art pléistocène dans de monde, Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarascon-sur-Ariège, septembre 2010, Special issue, Préhistoire, Art et Sociétés, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées LXV–LXVI: 152–153 (879–893 on CD).

Pancholi, R. K. 1994. Bhanpura kshetra me navin shodha. Purakala 5(1–2): 75. RAR 31-1135

31-2kumarkrishna-160120072350

Leave a Reply